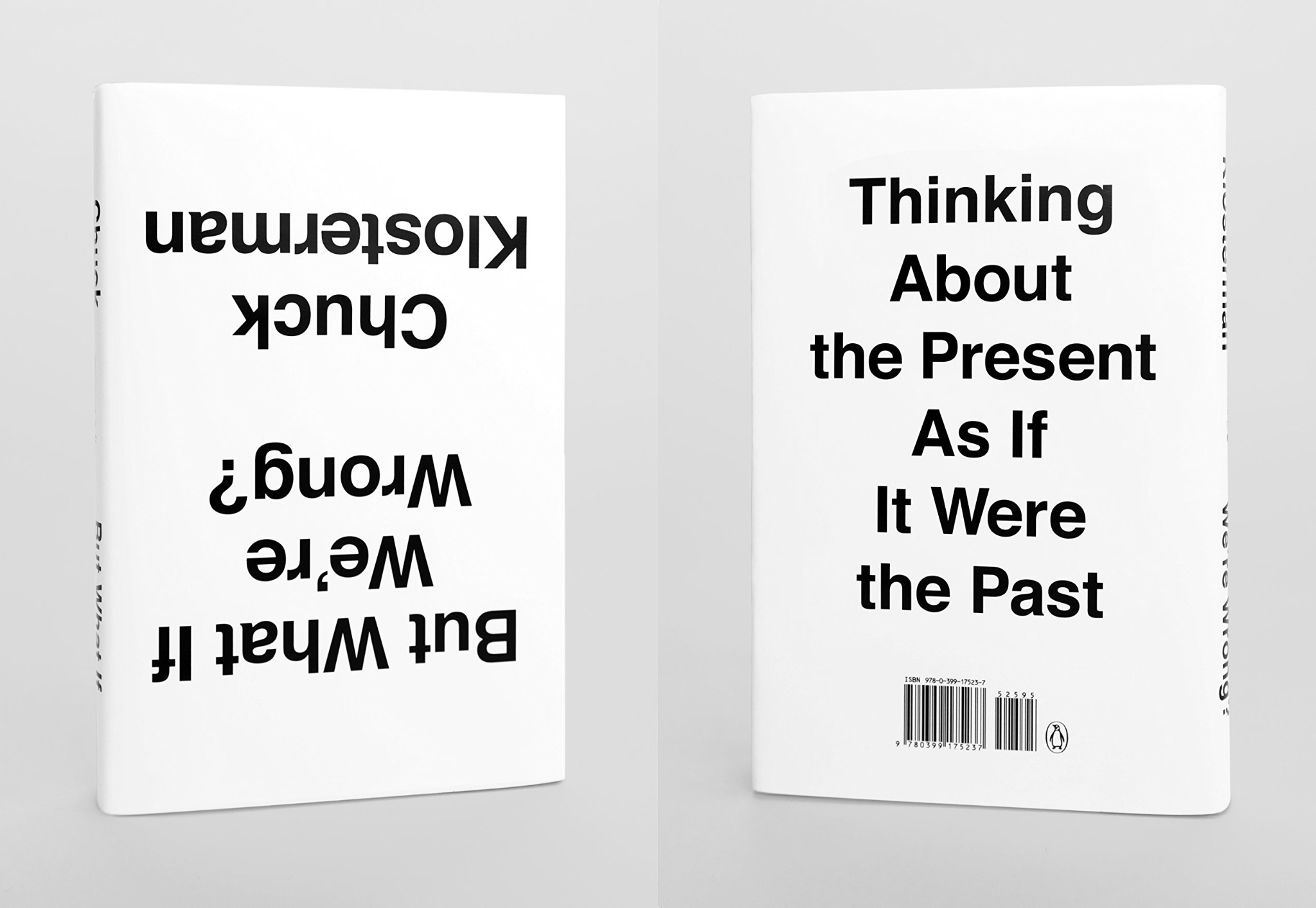

Chuck Klosterman: “But What If We’re Wrong?: Thinking About the Present As If It Were the Past.”

Perceiving the “now” through the future’s lens is undoubtedly a tricky, if not impossible, task. Yet, American pop culture essayist Chuck Klosterman attempts to leave no trending (and some, outdated) inventions and sociocultural affairs unchallenged. From gravity to literature, cinema to ideology, modern society has surely got some things right. But what if we’re wrong?

By Hana Anandira for Res Publica Politics, 2021.

For an offbeat analysis that piques the curiosity of anyone living in the 21st century, American author and critic Chuck Klosterman started his 2016 book “But What If We’re Wrong?: Thinking About the Present As If It Were the Past” with spot-on musings on gravity.

An ex-columnist for The New York Times’s “The Ethicist”, Klosterman began this monologue by meditating on Sir Isaac Newton: “Instead of claiming that Earth’s existence defined reality and that there was something essentialist about why rocks acted like rocks, Newton was advocating an invisible, imperceptible force field that somehow anchored the moon in place.”

Away from Aristotle’s interpretation which broke the silence on gravity and argued that to quote the book, “all objects crave their ‘natural place’” and “a dropped rock fell to the earth because rocks belonged on earth and wanted to be there”, Newton’s discovery that followed a millennia later is plausibly more complex and—depending on the technological advances of that era—scientifically involved. After Newton introduced Principia to the world, people of the 16th century (and three more centuries that followed) thought they had arrived at gravity’s end. But when Einstein declared that gravity is beyond a force that somehow anchored the moon in place, but a distortion of space and time, they realised that they were mistaken.

They also realised that it has revolutionised science after hundreds of years of unexplainable vacuum. This contemplative introduction boils down to a single question: If mankind had misunderstood nature’s most fundamental theory for centuries—one which we believe had put man in place—what about the other things on which we have claimed to be right?

Also the author of best-selling “Sex, Drugs and Cocoa Puffs: A Low Culture Manifesto” (2003), Klosterman fixed his lens on tomorrow to explore the probability of today. Spreading 288 pages, “But What If We’re Wrong?” unravels provocatively as the essayist traces from one subject to another with a pragmatic and witty approach, peppered with personal anecdotes that amplify the dialogue. Probing the theme of ‘collective consciousness’ and how science and arts readjust to social changes in each passing generation, Klosterman tapped bravely into the objective in which “any present-tense version of the world is unstable”, and that “reevaluating what we consider ‘true’ is becoming increasingly difficult” by revisiting the cultural mishaps history had encountered.

To wit, his observation of the earth’s gravity, which functions as an entry to how the book takes off, connects us to the following chapter that examines a pivotal turn in literature—one that upended the status of a late author and redefined what makes a novel: Herman Melville’s “Moby-Dick” (1851). A declining literary work that eventually made it after the author’s death. “For the next thirty years [after Melville’s demise], nothing about the reception of this book changes. But then World War I happens, and—somehow, and for reasons that can’t totally be explained—modernists living in postwar America start to view literature through a different lens. [...] The concept of what a novel is supposed to accomplish shifts in his direction”, Klosterman wrote.

With the advance of time, the collective wrongness and errors of judgment society have imposed on many events continue to subvert and surprise, and Klosterman’s observation may well remind us of an extreme case (which has now probably passed as a cliché) that marked a critical point in history: Donald Trump.

From the late ‘90s up to the year 2013, Trump made frequent appearances on the World Wrestling Entertainment; the grandest stage of sports entertainment at its time. Outside of the show-biz firebrands that benefit from his media ubiquity and business organisation, nobody really takes him seriously. In 2017, however, he hiked up from being a media mogul to America’s first man—later catching up with Putin and Kim Jong-Un in 2019.

He became such a powerful (but nonetheless, comical) phenomena that the suffix “ism” is now attached to his last name; a dogma that well outlived his controversial presidential term.

Besides that it’s telling of how anything can happen in the age of capitalism, internet, and press-political power, the above case—though it does not necessarily stand in line with the case of gravity or literary transformation that shifts from wrong-right or right-wrong—proves true to the present state where the future has become much more unpredictable despite all the advancements that many hope would bring some sense of clarity, and the overwhelm of information striving for validity has left much to desire.

Reminiscent of Harari’s introspective style at first blush, Klosterman’s unique and somewhat satirical takes on culture would also captivate those familiar with works of late Mark Fisher. And for Klosterman, a journalist who has written for publications like Esquire and Rolling Stone, words matter. So expect the author to examine the word “book” and ponders upon the authority of language (it’s probably worth remembering that the word “record” now refers to any collection of music regardless if it’s played on vinyl or not, and the term “moon-landing” is regarded more religiously and politically by Americans after Soviet launched Sputnik) before he moves on to parsing the century’s standardisation of ground-breaking literature in his quest to uncover the contemporary Kafka—who will most likely be discovered in the distant future when he, too, failed to outlive his works.

The topics stretch far, all analysed by the author as he put himself on the other end of today through a logic he aptly named Klosterman’s razor (a tongue-in-cheek contrast to Occam’s razor): “the philosophical belief that the best hypothesis is one that reflexively accepts its potential wrongness, to begin with.”

Thus, since this article’s purpose is to underline why the book might be crucial in what Slavoj Žižek coined as the post-ideological era (where oppression and struggle to search for meaning suffocate under the banners of liberalism and dreams for democracy), the unpacking of Klosterman’s razor-sharp cultural observations are unnecessary to be explained in detail. But perhaps one of his unerring questions is enough to kickstart a personal cross-examination on the world at large: “Have we reached the end of knowledge?”

While deconstructing the future’s sociocultural state is remotely impossible, Klosterman attests that this experimental (and philosophical) mind-wandering can only be achieved through meditating on the things we fail to examine, no matter how seemingly unimportant they are.

“In the early 20th century you had Freud and Jung analyzing the symbolic language of dreams, and an artistic movement, surrealism, that drew inspiration from dreams. [...] As a teenager, I kept a detailed dream diary. Maybe it’s just our family, but it doesn’t seem like my kids ever talk about their dreams. It’s just not something people pay much attention to anymore. Why is that?” asked writer Simon Reynolds to Klosterman in an interview for The Guardian, to which he replied, “Freud and Jung were the apexes of looking at dreams seriously. But more recently you have scientists who map the brain, like these two guys at Harvard who came to the conclusion that dreams are just leftover thoughts from the day. . . The conclusion of all this neurological research was that the content of dreams is worthless. . . But I wonder if that’s a huge misstep. I understand the rational argument against dreams, but something feels important to me about them.”

Whether we have reached the end of knowledge is anyone’s guess, but the message behind this fragment of interview holds crucial as to how trivial things like dreams once swayed a powerful influence and are now, by means of cultural shifts, slowly losing their value. Hence, the book sets in stone a casual, yet psychological nuance that drives one to ponder and retrospect about discovery and rediscovery, expirations and revivals, and ultimately, what makes something perpetually impactful regardless of any climate; like the way The Beatles reigned memorable or how Frank Lloyd Wright built timelessness into existence.